WannaCry Ransomware

Beginning on Friday, May 12, 2017 a new, previously unknown strain of Ransomware began.

Somewhere in Europe, an unwitting computer user opened an email and an attachment to that email, a compressed zip file, allowing WannaCry into their system.

Before it began to scramble the contents of that machine’s hard drive, and then later those of at least 200,000 others at hospitals, oil companies, banks and other organizations around the world, WannaCry had a small piece of housekeeping to perform.

A command in WannaCry’s code told it, each time it infected a new machine, to try to communicate with an obscure web address: a long string of characters seemingly created by someone running their fingers across a keyboard. The domain was inactive, the communication failed, and so WannaCry’s code told it to carry on.

This initial step would later prove to be the attack’s Achilles heel, but for the first few hours, it would go unnoticed and WannaCry would be left to propagate unhindered.

Phase two of that first WannaCry infection was to find out what file-sharing arrangements the computer had, and begin exploiting them.

To do so, it deployed its secret weapon — or rather, a weapon that had once been someone else’s secret: a repurposed cyber spying tool known as EternalBlue, stolen from the US National Security Agency and leaked online.

EternalBlue exploits a security loophole in Windows operating systems that allows a malicious code to spread through structures set up to share files — such as dropboxes and shared drives for documents or databases — without permission from users.

“The widespread use of filesharing between organizations is to some extent a dream come true for a cyber criminal,” says Darren Thomson, chief technology officer of Symantec, the anti-virus and web security company. “If you can exploit a filesharing vulnerability, then you can get to tens or even hundreds of thousands of users.”

Spain’s Telefónica, the mobile phone operating giant, was among the first to announce publicly it had a problem. By mid-morning, employees across the company were finding themselves locked out of their work terminals. Telefónica subsidiaries in Portugal and in South America were affected too.

In Britain, the impact of WannaCry was far more serious. At about 11am, the first hospitals in the UK began to report a ransomware attack to the national cyber incident response center. By lunchtime, emergency services were being pulled and hospital facilities across the country were brought down.

The list of infected organizations would swell dramatically in the next few hours: Chinese petrol stations operated by the state oil company had payment systems cut off; German railways lost control of their passenger information system; and FedEx’s logistical operations were disrupted.

Cleaning up the mess and trying to work out the scale of the threat and how it spread is no easy task. “We’re still digging but the people with the best data — the victims — are basically burnt to the ground and have more high-priority items at this point than figuring that out,” said a senior US cyber researcher.

Security analyst’s stress it could have been worse but for the actions of an anonymous British security researcher. After lunch on Friday, a 22-year-old cyber analyst, who writes online under the pseudonym MalwareTech, returned to his desk and spotted something crucial in WannaCry’s code — the first stage of its infection process. The obscure web address the ransomware was querying, he noticed, was unregistered and inactive. So he bought it for $11 and activated it.

It turned out to be a form of “kill switch” baked into WannaCry by its creators. Activating the address told the ransomware, upon each new infection, not to proceed any further. Once he had control of it, WannaCry was stopped in its tracks.

Comment: If not for the researcher discovering the unregistered web site, this could have been way worse than it was. You cannot emphasize strongly enough to your staff to delete any email that they do not recognize.

Updated: Multiple security researchers have claimed that there are more samples of WannaCry out there, with different 'kill-switch' domains and without any kill-switch function, continuing to infect unpatched computers worldwide.

So far, over 237,000 computers across 99 countries around the world have been infected, and the infection is still rising even hours after the kill switch was triggered by the 22-years-old British security researcher behind the twitter handle 'MalwareTech.'

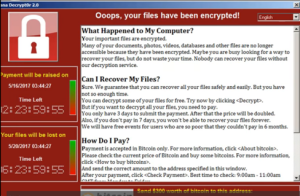

Here is a screenshot of what you will see after your files have been encrypted:

Texas Health System Settles Potential HIPAA Violations for Disclosing Patient Information

Memorial Hermann Health System (MHHS) has agreed to pay $2.4 million to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and adopt a comprehensive corrective action plan to settle potential violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. MHHS is a not-for-profit health system located in Southeast Texas, comprised of 16 hospitals and specialty services in the Greater Houston area.

The HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR) initiated a compliance review of MHHS based on multiple media reports suggesting that MHHS disclosed a patient’s protected health information (PHI) without an authorization. In September 2015, a patient at one of MHHS’s clinics presented an allegedly fraudulent identification card to office staff. The staff immediately alerted appropriate authorities of the incident, and the patient was arrested. This disclosure of PHI to law enforcement was permitted under the HIPAA Rules. However, MHHS subsequently published a press release concerning the incident in which MHHS senior management approved the impermissible disclosure of the patient’s PHI by adding the patient’s name in the title of the press release. Also, MHHS failed to timely document the sanctioning of its workforce members for impermissibly disclosing the patient’s information.

In addition to a $2.4 million monetary settlement, a corrective action plan requires MHHS to update its policies and procedures on safeguarding PHI from impermissible uses and disclosures and to train its workforce members. The corrective action plan also requires all MHHS facilities to attest to their understanding of permissible uses and disclosures of PHI, including disclosures to the media.

The resolution agreement and corrective action plan may be found on the OCR website at http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/compliance-enforcement/agreements/MHHS/index.html

Rick Boyles

rick.boyles@computernetworksinc.com

757-333-3299 x200

TheDarkOverlord Honors Threat, Exposes 180,000 Patient Records

The hacker had warned Aesthetic Dentistry and OC Gastrocare in 2016 to pay to keep the records private, but the extortion attempt failed.

Dark Web hacker TheDarkOverlord has released 180,000 patient records from three hacks, DataBreaches.net revealed Thursday.

More than 3,400 patient records were released from New York City-based Aesthetic Dentistry, 34,100 from California’s OC Gastrocare and 142,000 Tampa Bay Surgery Center.

TDO used a Twitter account to post a link to a site that allows any user to download the patient databases from these organizations. The hacker has a history of using Twitter to shame the organizations he or she has breached.

The hacker warned Aesthetic Dentistry and OC Gastrocare in the fall on Twitter that he or she was in possession of the data as a means to extort these organizations into paying to keep the data private.

Many of the databases contained a trove of patient data including medical conditions, insurer details and, for some, Social Security numbers, dates of birth and payment information.

None of these organizations appear on the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights’ Breach Portal.

In 2016, TDO breached Little Red Door Cancer Services of East Indiana, PilotFish, Athens Orthopedic Clinic and Peachtree Orthopedics last year - among others. TDO also breached an unnamed health insurer and listed 9.3 million records for sale on the dark web in 2016.

Security Risk Analysis Deadline Under ACI Is 12/31/2017

A routine audit conducted by Virginia Mason Memorial has revealed employees have been accessing the protected health information of patients without authorization.

Audits of PHI access logs occasionally reveal rogue employees have been improperly accessing the medical records of patients, but what makes this incident stand out is the number of employees that were discovered to have improperly viewed PHI. The audit revealed 21 employees had deliberately accessed PHI without authorization. Virginia Mason Memorial conducted the audit in January and immediately terminated access to PHI to prevent further privacy breaches. The investigation revealed those 21 employees had accessed the PHI of 419 patients. All of the patients had visited the hospital’s emergency room. The investigation was conducted internally, although the hospital also brought in a third-party cybersecurity firm to conduct a forensic analysis of its systems. That firm has also been searching the darknet to find out if any of the accessed records have made it onto darknet marketplaces. To date, no patient information appears to have been listed for sale.

A spokesperson for the hospital issued a statement saying, “We believe this to be a case of snooping, or individuals who were bored.” The hospital does not believe the records were accessed with malicious intent. As a precaution, all affected patients have been offered credit monitoring services without charge.

The incident shows how important it is for healthcare organizations to conduct regular audits of PHI access logs to identify privacy issues before they become a major problem, and the importance of not only providing training on HIPAA Rules and patient privacy, but also regularly reminding employees of the requirements of HIPAA and the penalties for improper PHI access.

You should be reviewing YOUR EHR logs for similar behavior by your employees. Accessing records without a need (snooping) is a HIPAA violation.

A computer lets you make more mistakes faster than any invention in human history – with the possible exceptions of handguns and tequila.

Computers make very fast, very accurate mistakes.

Q: How many programmers does it take to change a light bulb?

A: None. It’s a hardware problem.